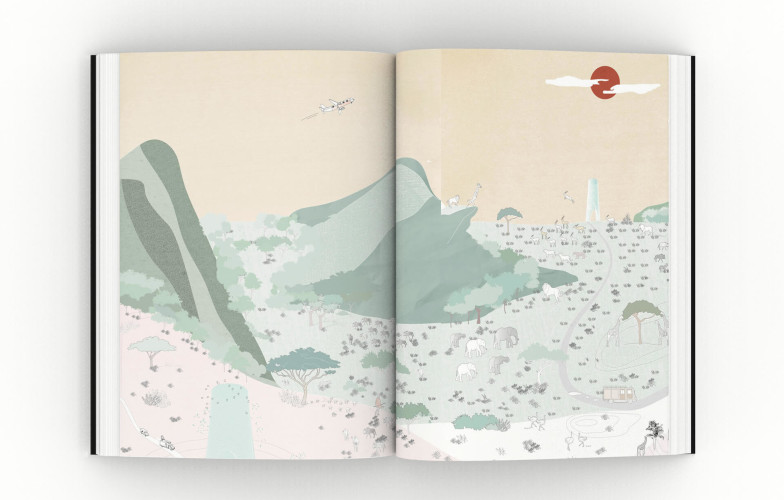

“During the spring of 2020, in the midst of a global pandemic, Berlin Tegel ‘Otto Lilienthal’ Airport looked like a stranded spacecraft. Once a symbol of the fluid mobility of the West and an hommage to both the automobile and the aeroplane, the crowded airport was suddenly completely empty, offering unobstructed views of its singular architecture and myriad of improvised structures…”

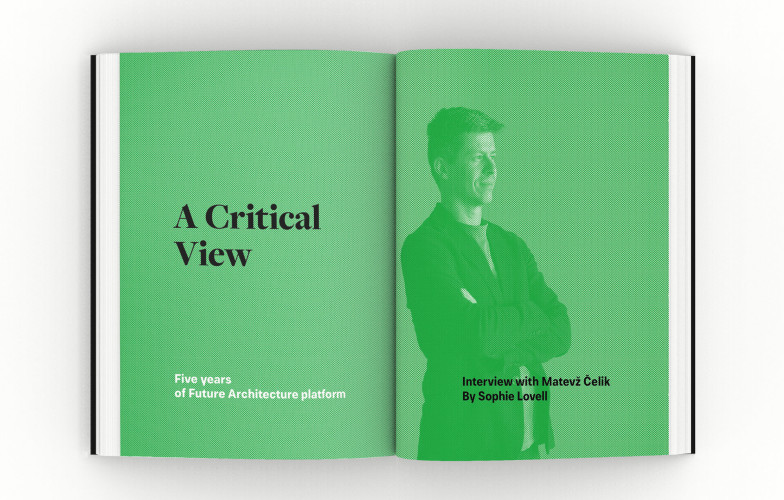

TXL The Drive-in Airport

When writing about buildings in Berlin, one is always very conscious of their place in the historical fabric, whether they were damaged or destroyed during the WWII and then rebuilt or repurposed; whether they fill a gap crated by bombs or policy; whether they have a compromised historical past; or whether they had some particular additional representative function when the city was divided between 1946 and 1989. The story of Berlin Tegel “Otto Lilienthal” Airport, to give it its full name, or TXL, to call it by its IATA code, is a classic Berlin city planning and architectural tale in this respect.

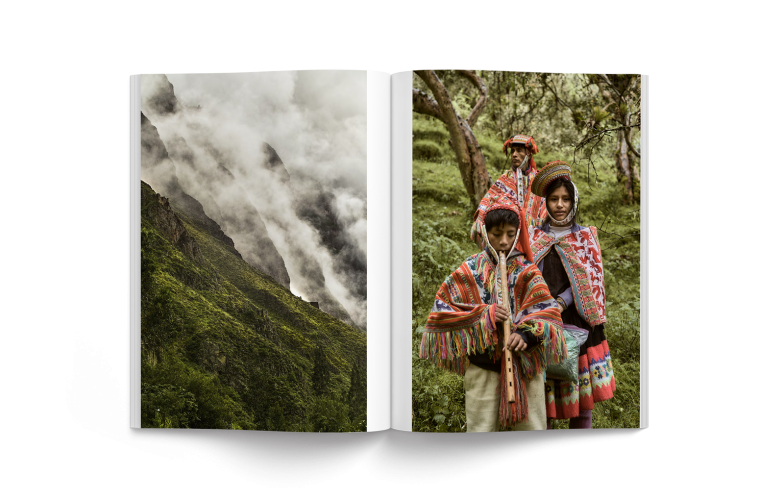

After WWII and up until 1989, West Berlin was an island in Cold War Europe that was predominantly connected to the West through the umbilical cord of an “air corridor”, through which people and provisions got in and out to other Western states by air. There was a road route, but it meant travelling through GDR-controlled territory and submitting yourself to checkpoints. Since many residents of West Berlin were refugees from “the East”, this meant their only safe route in and out was by plane. This air route had mythological status from early on thanks to the Stalinist Soviet blockade, which forced the three Western Allies (France, USA and Great Britain) to supply the entire city of two million residents by air alone between June 24, 1948, and May 12, 1949, in an endeavour that became known as the Berlin Airlift.

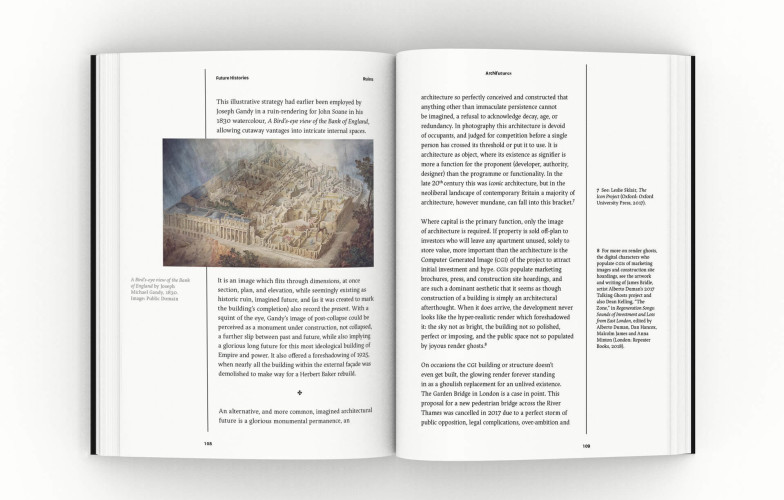

By the time the 1960s arrived, along with the Berlin Wall, the Jet Age was in full swing and civil traffic was of increasing importance despite no end to the Cold War in sight. It became clear that the air route into Berlin was in need of modernising. West Berlin needed a new international airport: a modern gateway to the rest of the West. But, West Berlin was tiny and suitable location options were in very short supply. There was only one big, high-capacity airport in West Berlin: Tempelhof Airport, which was close to the city centre. But Tempelhof’s runway was now too short for increasingly modern aircraft and long-haul or fully-laden flights could not land and take off there. It was also built by the Nazis and looked like it, so it was not really the ideal new face of international travel for Berlin. There was another smaller airbase in the British sector in the South West of the city but its runway was also too short. In the Tegel district, in the French sector, in the northwest of Berlin, however, was a long enough runway to take big international jets. The runway itself was an extraordinary feat of building in its own right: it was constructed mostly by hand in 1948 during the Soviet blockade in just 90 days by tens of thousands of Berliners, half of whom were women.

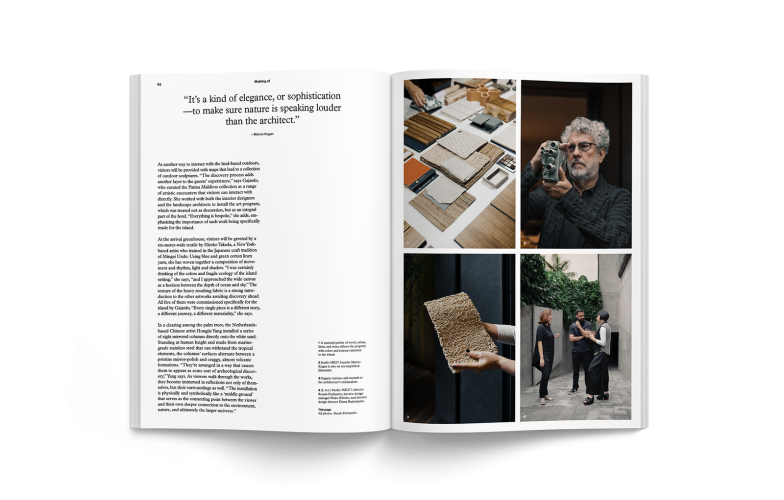

A suitable runway had been found, now all that was needed was an international airport to go with it. So in the mid-1960s, an international competition was held to design it. Architecture practices from all over the world entered their designs, but the winners of the competition were a pair of young German architects barely out of grad school who had not built anything of any significance to date and barely had a proper office: Meinhard von Gerkan and Volkwin Marg. It was quite a sensation at the time. Today they are better known as Gerkan, Marg and Partners (gmp), and their firm has 13 offices worldwide and over 300 employees. They have designed a myriad of important buildings since, both worldwide and in Berlin, including two other great transport gateways to the city: the massive multi-level Hauptbahnhof (central station) and the infamous new Berlin Brandenburg Airport “Willy Brandt”, International Airport, known to all as BER (Bay-Ay-Air) built to replace TXL and opening nine years behind schedule – but that is another story. But back in the mid-sixties, when they won the Tegel competition, they were terra incognita.

“It was our first big project”, explains Volkwin Marg, now 84. He and Gerkan had studied together in Braunschweig and earned money to support themselves by doing competition drawings for other architects. After graduating, they rented a room together in Hamburg and continued doing competition drawings with other architects, but this time under their own names and as project partners. It turned out to be a winning combination, “Basically, we shot from the hip and hit the target”, explains Marg, “We won seven of them in total that first year, which was sensational, and the largest of these was the international architecture competition for Tegel Airport.”

As luck would have it, Gerkan had just finished his university thesis on a new design for Langenhagen airport in Hanover and had therefore intensively studied the theme of airports for his final year project. So they already had a great deal of research on this highly specialised architecture topic under their belts. Nevertheless, they could not believe their luck: “It was, of course, a huge surprise and a great joy”, remembers Marg, “a unique chance for us and for Berlin at the time – epochal”.

Since they had somehow managed to award this commission to a pair of unknowns with no other airport references whatsoever, instead of to a large, experienced, high-capacity practice, representatives from the airport company decided to visit von Gerkan and Marg (and another university friend Klaus Nickels, who was in on the project too) in their office in Hamburg and gain an impression of who they were working with. “We were a tiny office!” recounts Marg. “So we very quickly upgraded the rented apartment we were working in with lots of tabletops, that we made white covers for. Then we brought in lots of T-squares and lots of friends that we dressed in white coats, who then stood there moving rulers around and drawing, all to give the impression of a functioning architecture office.”

Gerkan and Marg brought in another partner architect for the project, called Rolf Niedballa, who had experience in managing contracts and bids. “He had the advantage of being a bit older than us and already experienced as a construction supervisor”, says Marg. They also had the good fortune of having a highly experienced client: “The airport company were of course just the users, and they were smart enough to hand over the actual building of the airport to the Berlin Hochbauamt [Department for Building and Housing]: a public authority that really understood how to build and was qualified to be the client”, he adds, “This is a great difference to just letting planning happen – as was the case with the BER airport that we planned [much] later. There it was the airport operator, who was not at all qualified [to be the client].”

Nevertheless, the Tegel project, completed in 1974, was huge and the client wisely commissioned the airport terminal and all the ancillary buildings from Gerkan, Marg and Partners in stages, “one on top of the other: first the terminal, then the front end of the terminal, then the separate power station, the hangars, then the whole frontage development: baggage, customs, fire brigade etc., – everything that belongs to an airport.”

For passengers that have travelled via the original terminal building at TXL (not the later, tacked on tin-clad hangars added when capacity was bursting at the seams because completion of its new replacement, BER, was interminably delayed), it is a surprisingly unstressful experience. Many of my frequent flier colleagues profess a great affection for Tegel because it is “so easy” but few stop to think about why. It certainly does not have much to do with looks. TXL is as brutalist as they come, horizontal, low-slung and fixed firmly on the ground. There are no light and airy allusions to flight in the design whatsoever. But behind that impression of easiness is deliberate intent: Tegel Airport is completely dedicated to the passenger.

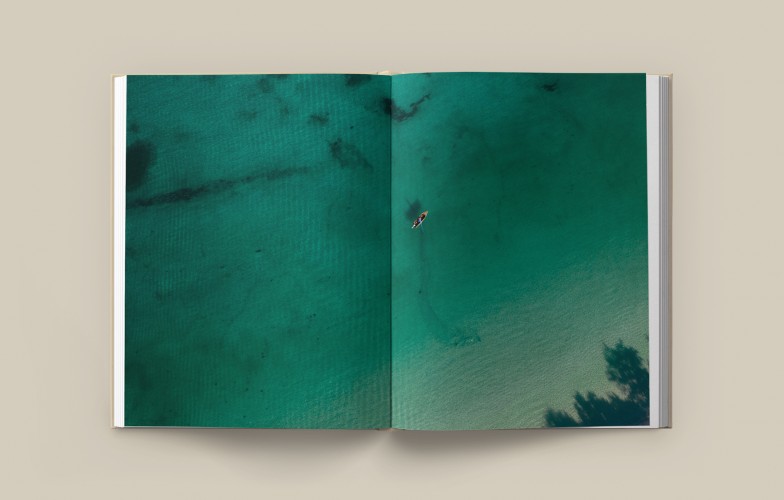

Designed as it was in the mid-sixties, TXL is also an airport that is geared towards the age of the automobile – as the ultimate representation of freedom. A popular slogan in Germany back then was: “Freie fahrt für freie Bürger!” (free driving for free citizens). The genius of this airport design is that it creates essentially the thinnest feasible interface between car and plane. If you look at an aerial view, you can see clearly that its form is designed to bring two sides together with the shortest possible distance in between. There is an “air” side for the movement of the airplanes, including take-off, landing, taxiways, apron and parking positions Marg describes as “just like ships at a quay – but nose-in”.

On the other side of the interface, which is the gates, is a building for cars. When it was built, you could drive right up to your check-in. “In other airports you had to park your car, enter the terminal and then cover long distances per pedes to your aeroplane”, says Marg. For him and his partners, the greatest imaginable luxury would be to drive directly to where your plane is parked and there check in your luggage, show your passport, get your boarding pass, walk through the gate and get straight onto the plane. So that is what they designed: “A totally decentralised checking-in system with the shortest distances that had ever been built.” The distance between the drop off point with the car and the counters is indeed no longer than 30 metres. TXL is a drive-in airport.

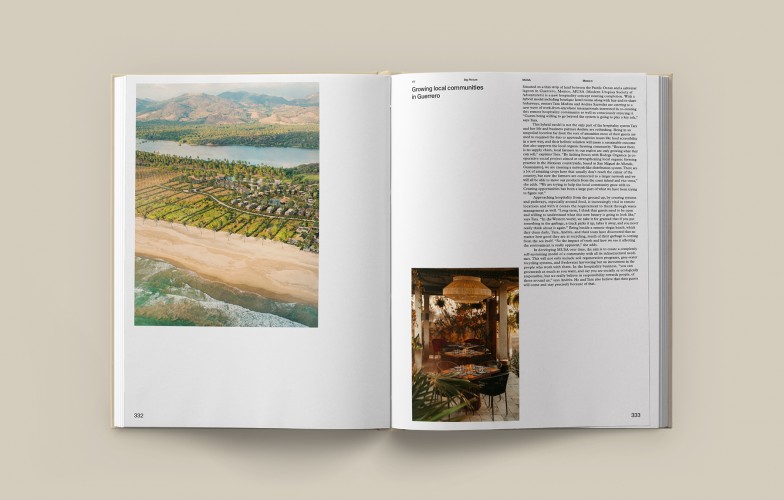

With this aim of a decentralised, slim interface in mind, the logical solution was to create a ring-shaped design. To make it efficient, the ring was turned into a polygon, which led to the architects choosing an overriding hexagonal geometry to facilitate routing and configuration of the approach roads, “since it is easier to drive through forks than T-junctions”, says Marg. The original plan had a large hexagonal car park in the middle that was only partially realised.

“There was also another reason for that form”, adds Marg, “the design was made before we had computers and the architect’s main tools were the parallel ruler and the set square. If you use the triangle which has a 60 degree and a 30-degree angle, you can design hexagonally very quickly. If you were trying to design a free form back then like [Hans Scharoun’s 1963] Berlin Philharmonie, then nothing repeats itself and it is infinitely more complicated in every respect.” The young architects must have been very aware of the older architect’s struggles to build and complete his iconic and highly experimental concert-hall-in-the-round at the time they were creating their airport design.

When the airport was completed in 1974 there was no end to the Cold War in sight and hence no expectation of any change in territory size for tiny West Berlin. Nevertheless, the architects had designed TXL with expansion in mind. The idea was to double capacity by building a second hexagonal ring joined to the first by the main building with its tower, like a pair of spectacles. But the second ring was never built and Tegel remained a monocle that later gained provisional extensions that had nothing to do with the original decentralised principle.

The decentralised design of the TXL terminal was all about how to save the passengers time; how to save them from walking long distances and long waiting times. Instead of the passengers doing the walking, the airport staff had to walk to them and their gates to attend to each plane-load as they embarked or disembarked. The terminal’s primary function was to get people from their cars to their planes and planes to cars as comfortably and efficiently as possible. Mass transport on the land side was never really a big consideration. You can travel by bus to Tegel Airport, but there are no train or underground lines to it. The thinking was probably that if you could afford a plane ticket, you could afford to pay someone to drive you to the airport or to pick you up. And anyway, who didn’t have a car?

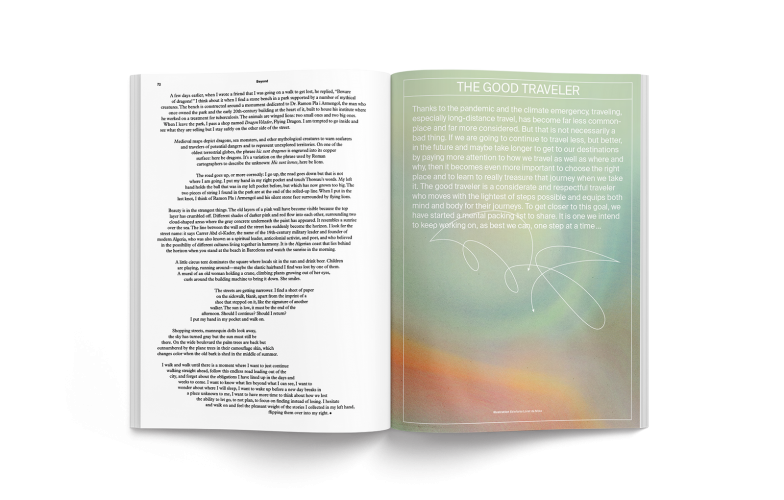

Since TXL was built, almost half a century ago, much has changed in the global economy, air travel and airport design as well. The subsequent rise in neoliberal capitalism has meant that travel hubs are no longer just for getting from A to B, but have primarily become retail opportunities. Since 9/11 too, anti-terrorist security controls have also massively changed airport structures. In today’s generic international airport, passengers are funnelled into central security areas where they and their luggage are screened for potential hazards. Instead of the customer being king, they are essentially treated as walking danger zones that could be carrying, bombs, weapons or disease. Once the screened and tagged passengers are all through the queues and discomfort of central security control, they are then squeezed again through a large retail area in an attempt to relieve them of as much of their money as possible by encouraging them to buy things largely unrelated to their journey. There they wait, in the shopping mall, until being told where to board their planes, whose gates are often a (very) long walk away.

This is exactly what did not happen at Tegel Airport and this is why passengers, however subconsciously, loved it. It was an airport experience where you were not treated like cattle. “It was never done as perfectly again as it was in Tegel”, says Marg. “The times have sadly changed. We now stand under the dictatorship of consumption, and airports stand under the tyranny of having to earn their money through retail because the airport fees are not sufficient. And on top of that terrorism has forced total control.” Air travel will never be the same again. And perhaps that is also why many mourn the passing of TXL as an airport. COVID-19 and global pandemic control is a new factor that is not going to go away in the foreseeable future. And with the climate emergency, it now looks the Jet Age is well and truly over. Flying in the future will be something completely different and architects will need to design completely different buildings for it. Hopefully though, whichever form they take, those buildings will be primarily in the service of the passenger, as TXL was: a beautifully designed, drive-in airport for a bygone age.

Sophie Lovell, November 2020

Flughafen Tegel

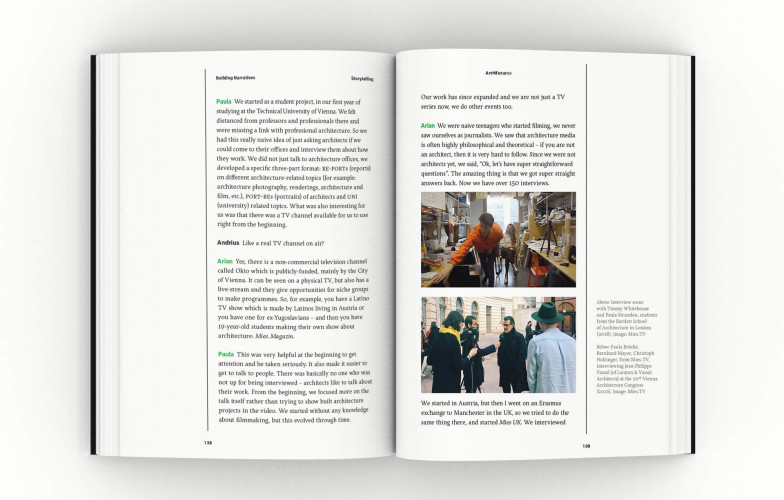

Photographs by Felix Brüggemann and Robert Rieger

Essay by Sophie Lovell

Graphic design by Maximilian Mauracher and David Rindlisbacher

Proofreading by Anne-Christin Schubert

Published by POOL