We have entered an age where the boundaries between creative disciplines have become noticeably porous and where new technologies, materials and processes alter our environments with a greater frequency than ever before. The rules that govern how we furnish our living spaces are in the process of being rewritten – at least for those living within the technological development bubble. Furnish seeks to document new work from pioneering designers, artists and architects exploring new domestic territories. This work moves beyond the pre-kindergarten aesthetic of “blobjects” or the stripped down worthiness of “new functionalism” of the nineties and signals a more developed sense of playfulness, and irreverent thrift as well as the beginnings of a new vocabulary of form.

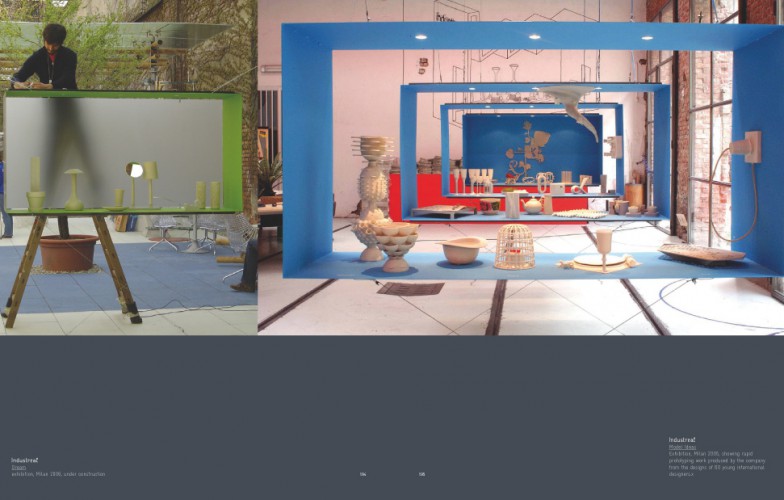

Design has become a catch-all term that can no longer be pigeonholed into discrete disciplines. In fact all the creative fields are in sore need of a new vocabulary to match the vagaries of its protagonists. It is not unusual, for example, to find architects engineering tables, artists designing tree houses, graphic designers tuning sofas and jaded industrial designers developing conceptual products that have nothing to do with practical function.

A discipline tends to be limited by its tools, but when we have access to affordable tools whose application capacity extends way beyond their original mandate it is only natural to want to experiment. As computer sophistication and new technologies become increasing accessible to the individual, our capability to cross genres is dramatically expanded. Both consumers and designers are not just creating, editing and manipulating their own films, animations, websites and music, for example, but designing their own interiors, furniture, structures and objects as well with the aid of these technologies and the software that governs them. Far from making designers, artists or craftspeople redundant, this phenomenon seems only to be tending towards a further redundancy of categories and borders between disciplines. More of us are being more creative and more creatives are broadening their fields of activity. Interestingly, the role of the skilled professional is not being eroded as a result but their capacity for collaboration beyond the confines of their respective disciplines, should they choose to do so, has taken a quantum leap.

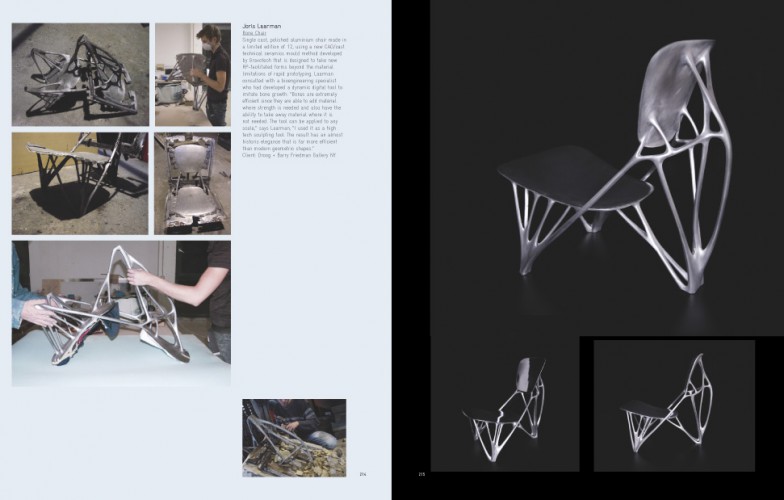

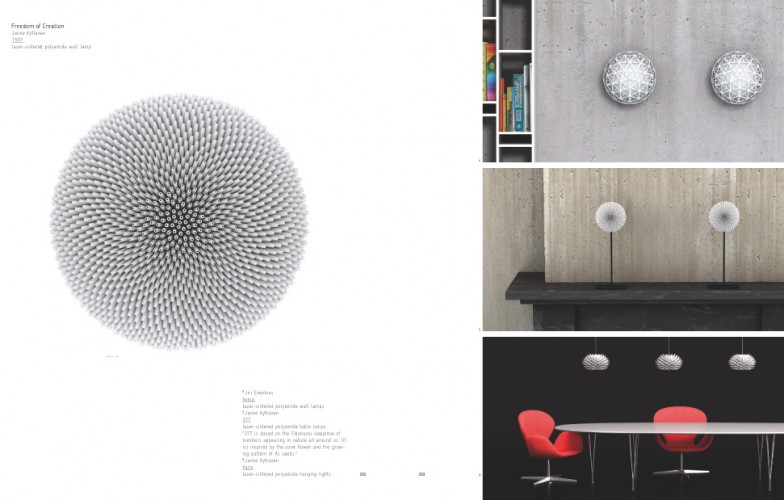

It is not just individuals that are discovering new opportunities beyond their conventional labels, object categories too are beginning to look increasingly wobbly: In this book alone, we find furniture as landscape; furniture as concept, as data, as interface, as digital-organic growth, as mutation or insertion. Furnish illustrates a babel of form that is breathtaking in its diversity from flatpack baroque or postmodern porcelain to strange neo-organic chimeras. Hybridisation and appropriation are key themes – opening up all the borders means abandoning rules of aesthetics and genre distinctions. Mixing hi-tech with retro elements, building in historical narrative or bootlegging the designs of others are all permissible. Only the laws of physics still apply: if you want to make a chair then it has to be structurally sound or you won’t be able to sit on it and it can’t therefore be a chair (unless of course it is a concept masquerading as a chair).