It is difficult to talk about the work of the artist James Turrell to someone who has not experienced it. Born in California in 1943, he has been working with light and optical phenomena since the 1960s, exploring the edges of human perception, where they meet what might be called spiritual experience, with the precision of a scientist, the lyricism of a poet and the zeal of a visionary. He builds structures for people to enter and experience the physicality of light, pieces of surprising delicacy with planes, fields or spaces that set free the mind of the viewer to construct their own castles in the sky from and intense, yet subtle photon palette. We told you it was difficult to talk about.

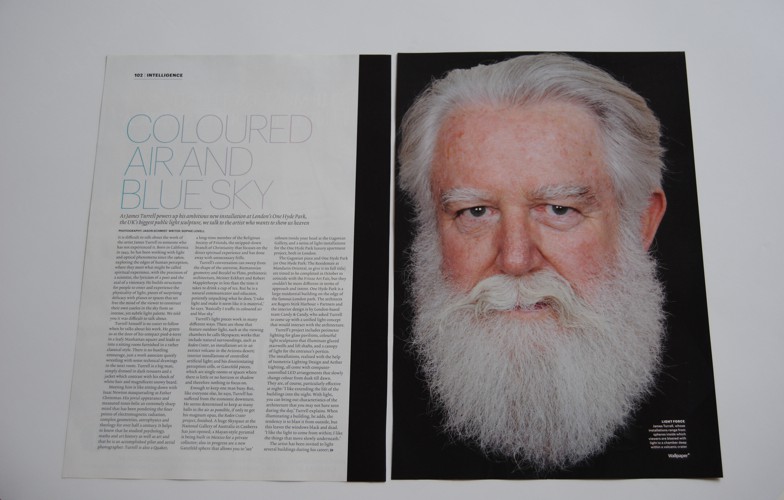

Turrell is no easier to follow when he talks about his work. He greets us personally at the door to his compact New York City pied à terre in a leafy Manhattan square and leads us into a sitting room furnished in a Quaker-built, rather classical style. There is no bustling entourage, just a work associate quietly wrestling with some technical drawings in the next room. Turrell is a big man, simply dressed in dark trousers and a jacket which contrast his shock of white hair and magnificent snowy beard. Meeting him is like sitting down with Isaac Newton masquerading as Father Christmas. His jovial avuncular appearance and patient, measured tones belie an extremely sharp mind that has been pondering the finer points of electromagnetic radiation, complex geometries, astrophysics and theology for over half a century. It helps to know that he studied perceptual psychology, mathematics and art history as well as art and that he is an accomplished pilot and aerial photographer. It is also important to know that Turrell is a Quaker, a member of the Religious Society of Friends (once termed “Children of the Light”), which is a stripped down branch of Christianity that focuses on the direct spiritual experience and has done away with what it sees as unnecessary frills and ceremony.

Turrell’s conversational threads can be both multidisciplinary and multifarious, sweeping from the shape of the universe, Riemannian geometry and Plato to prehistoric architecture, Bez Alel, Meister Eckhart and Robert Mapplethorpe in less than the time it takes to drink a cup of tea. But he is a natural communicator and educator, patiently unpacking what he does. “I take light and make it seem like it is material”, he says, “basically I traffic in coloured air and blue sky…”