These days when we talk about mid-century modern collectables, many of us are au fait with furniture designers such as Alvar Aalto, George Nakashima or Jean Prouvé, but what about the potters who made some of the era’s most defining vase forms: Pol Chambost’s sensual yellow curves, for example, Robert Lallemant’s architectonic shapes, or the fabulous Atelier Primavera’s glazes? Lets face it, when it comes to ceramics most of us can’t tell our lustre from our bisque. And whereas every home needs a decent vase or three we don’t often take the time to even appreciate the world of difference between a hand-thrown one-off and a mass-produced crock stamped out of a mould.

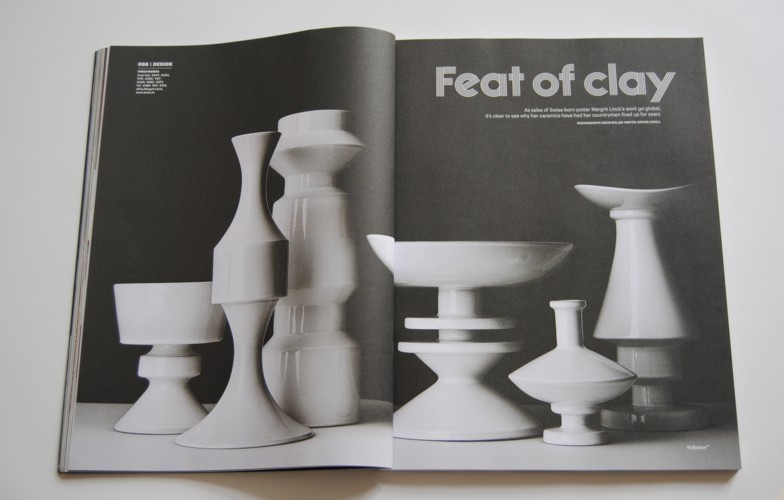

The grande dame of Swiss ceramics, Margrit Linck (1897-1983), is barely known outside of her home country. Her artwork ceramics change hands for modest prices amongst pottery enthusiasts, yet it is the powerful formal language of her domestic ware handmade in her home studio near Bern that has brought her an avid Swiss following since she chose to reject colour in favour of pure functional form back in 1941.

Margrit and her sculptor husband Walter Linck spent their early years in Bern before moving to Berlin in the 1920s and renting ateliers in Paris for the best part of the ’30s. Here they both soaked up the modern European artistic scene before returning home in the early years of the war. The influences Margrit brought back with her were primarily those of artists such as Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, and Joan Miro –she had little to do with contemporary potters of the time – and an abiding passion for African and South Sea Island sculpture.

Linck started producing gebrauchskeramik (domestic pottery) in the 1940s, deciding, as she said “to carry on where the old guard left off”. The early forms still echoed those of the local traditional pottery Heimberg, where she first learnt her trade, but she soon moved on into a stricter, more modern geometric language that has clear African influences but also looks forward to shapes later found in the Ettore Sottsass’ ceramic totems from the 1960s onwards.

Linck’s pieces, all thrown by hand on the wheel and glazed in either plain black or white, are highly technically demanding. They are baked for 48 hours apiece in two separate firings where the difficulty of getting an even glaze and avoiding cracks and faults is not inconsiderable. Since Linckâ’s death at the age of 96 in 1983, her small team of four part-time potters have continued turn out a maximum of 60 pieces per week in the tiny family workshop, all made to Linck’s exacting specifications…