The director of Ljubljana’s Museum of Architecture and Design (MAO) and organiser of the BIO Design Biennial, Matevž Čelik is an architect of a generation straddling the cultural divide between the state-socialism of former Yugoslavia and the burgeoning free-market economy of the young Slovenian nation. He spoke to Sophie Lovell about how the knock-on effects of political change have affected the country’s design industry and the difficulty of finding new models of engagement while hamstrung by the old.

You are a trained architect and had your own practice until 2010 when you took over the directorship of the MAO. What led you to take that step? What did you hope the museum would give you that designing buildings did not?

At the turn of the millennium, Slovenia was a country in which it was easier to carve out an independent career than elsewhere, but at the same time, architecture was produced and communicated in a way that was still deeply rooted in the past. As young architects building our first projects we strongly felt this gap. So in 2002, together with Dekleva Gregorič and Bevk Perović architects and others, we founded Trajekt Institute for Spatial Culture. Trajekt organized exhibitions and workshops and communicated mainly via the internet. It soon became a locus of architectural debate in Slovenia. I edited the Trajekt website and moderated discussions for eight years, so moving to the museum was a logical step in extending communication and reaching the general public.

From the nineteenth century onwards, during the period in which design as a discipline was taking shape worldwide, Slovenia went through several identity changes as a nation. How do you think this has affected Slovenian design – both stylistically and in terms of practice?

Design in Slovenia carries the genes of the Austro-Hungarian craft schools, the Bauhaus tradition as well as post-war socialist modernisation in Yugoslavia. It began with Jože Plečnik, who visited the Craft School in Graz and studied and collaborated with Otto Wagner in Vienna. Another key moment for the development of modern design in Slovenia was in 1961 when Edvard Ravnikar [Plečnik’s former student and Slovenia’s second most famous architect. Ed.] set up an experimental design course at the Ljubljana Faculty of Architecture. The course leaned conceptually towards the Bauhaus and the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, where Ravnikar collaborated with Max Bill. The course itself didn’t survive, but later the same methods were revived at the Department of Design at the Academy of Fine Arts, established in 1984. To this day, design in Slovenia has remained committed to modernist reductionism, subordination to function, ergonomics, and rationalisation for the purpose of mass production. The belief that the role of design in society should be connected to industrial production is still deeply rooted within the Academy’s product design department.

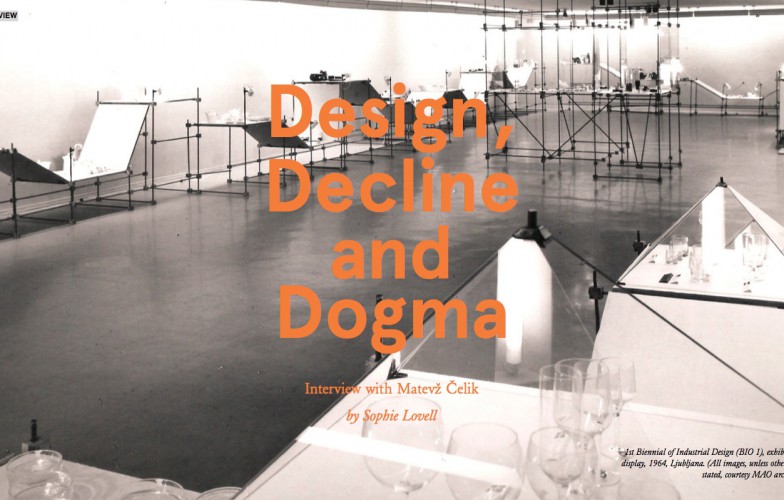

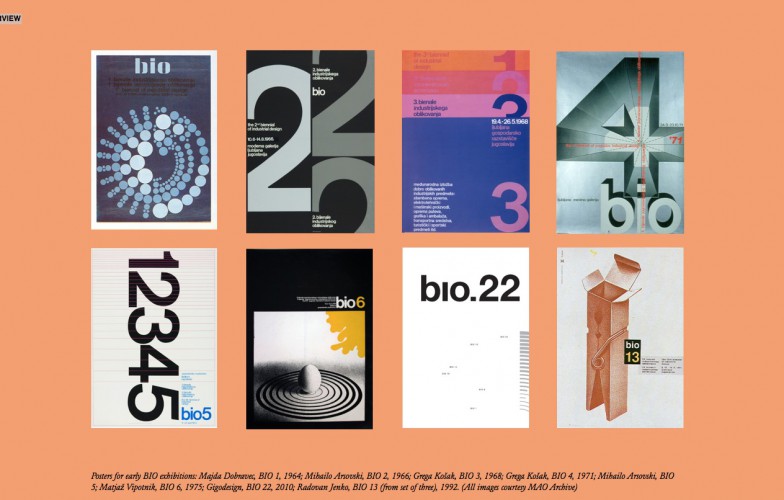

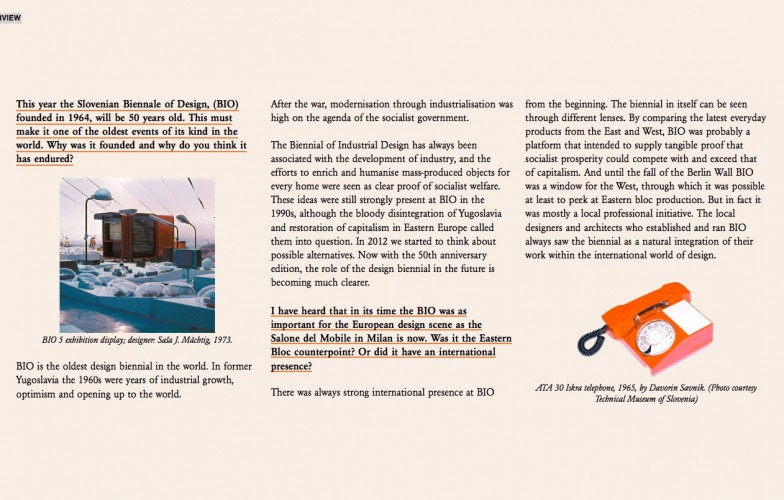

This year the Slovenian Biennale of Design, (BIO) founded in 1964, will be 50 years old. This must make it one of the oldest events of its kind in the world. Why was it founded and why do you think it has endured?

BIO is the oldest design biennial in the world. In former Yugoslavia, the 1960s were years of industrial growth, optimism and opening up to the world. After the war, modernisation through industrialisation was high on the agenda of the socialist government. The Biennial of Industrial Design has always been associated with the development of industry, and the efforts to enrich and humanise mass-produced objects for every home were seen as clear proof of socialist welfare. These ideas were still strongly present at BIO in the 1990s, although the bloody disintegration of Yugoslavia and restoration of capitalism in Eastern Europe called them into question. In 2012 we started to think about possible alternatives. Now with the 50th-anniversary edition, the role of the design biennial in the future is becoming much clearer.

I have heard that in its time the BIO was as important for the European design scene as the Salone del Mobile in Milan is now. Was it the Eastern Bloc counterpoint? Or did it have an international presence?

There was always a strong international presence at BIO from the beginning. The biennial in itself can be seen through different lenses. By comparing the latest everyday products from the East and West, BIO was probably a platform that intended to supply tangible proof that socialist prosperity could compete with and exceed that of capitalism. And until the fall of the Berlin Wall BIO was a window for the West, through which it was possible at least to peek at Eastern bloc production. But in fact, it was mostly a local professional initiative. The local designers and architects who established and ran BIO always saw the biennial as a natural integration of their work with the international world of design.

Many European countries are having to rethink their industries as manufacturing businesses struggle – and Slovenia is no exception. What used to be the key areas of industrial design and manufacturing in Slovenia and how are they faring today?

As the most developed and industrialised part of former Yugoslavia, with state-owned companies that had successfully exported to the West, Slovenia was well-placed in the 1990s. However, it responded wrongly to the challenges of economic transformation. The process of de-industrialisation in Slovenia coincided with the restoration of capitalism and the privatisation of state-socialist enterprises. Slovenia opted for a protectionist approach in which the government favoured the transfer of shares to local owners. It worked well for a time, but during this redistribution of power, rather than providing companies with visionary and responsible managers, a new economic elite emerged, who played primarily on their links with political parties and access to public money.

During these years the traditionally strong wood, furniture and textile industries virtually disappeared. Many factories no longer exist. Instead of investing in restructuring and modernising production, transactions over the last 20 years revolved within a closed circle of semi-state-owned banks and enterprises. When Europe entered the crisis, the Slovenian economy imploded and the cream of our companies were lost. On the other hand, now many new small companies are emerging, run by intelligent people who are looking for niche products, thinking long term, and enthusiastically developing their business models in accordance with social responsibility.

What problems need to be overcome?

In my opinion, one of the big problems in Slovenia is the expectation that big players or systems, either economic or governmental, will solve the everyday problems of every individual. Everyone wants to have a job but there are very few who think about how to create new jobs. If design is to develop, designers shouldn’t wait for clients to ask for something to be designed.

What areas and strategies of design are on the rise?

The design scene in Ljubljana is very lively. The young generation realises that the role and influence of traditional industrial manufacturers in the market have decreased. For instance, people gathered around a group called Rompom to organise “Pop-up Dom”, a flexible peer-to-peer network. This is replacing the rigid top-down production models designed to optimise the mass production industry in the last century. Crowdfunding platforms are just one of the tools that speak of new production models for our time. Designers act as facilitators and they organise co-working spaces or other services for designers. Another new initiative is Gigodesign’s recently launched Design Forward Accelerator, a service that includes seed money in cash, services, workspace and mentorship. Crisis also acts as a powerful engine for change in design.

How big a role do natural resources and materials and local skills play in contemporary design in Slovenia?

Wood, glass, textiles, metalworking, and also expertise in the chemical industry, where new materials are developed, have always been important for Slovenian design. In the past, it was the manufacturers who dictated the use of these materials. Over the last two years, MAO has presented the exhibition Silent Revolutions at various design events around Europe, which showcases contemporary design from Slovenia. The products in the exhibition show that designers are the ones increasingly suggesting the use of natural resources and local skills to producers.

What direction would you like to see the BIO take over the next 50 years and what role do you wish the MAO to play – in short, where would you like to take it?

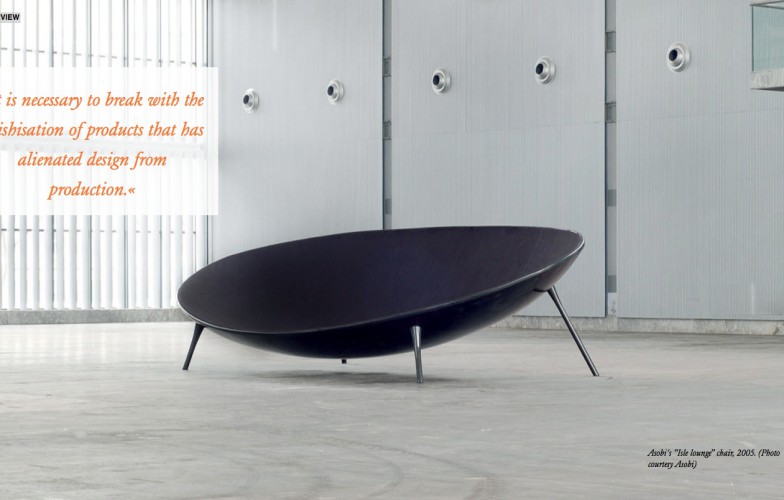

Right now we are facing the challenge of finding new solutions with almost no available resources for research and development of new models within existing economic structures. Production has been divorced from expertise and the two need to be reconnected. It is necessary to break with the fetishisation of products that has alienated design from production. I believe that BIO should play a role in this field and strive to support creativity in its most delicate and vulnerable stage. This means that in the future, BIO has to increasingly play a research-based, experimental role.

From uncube magazine issue no.18: “Slovenia”, edited by Sophie Lovell