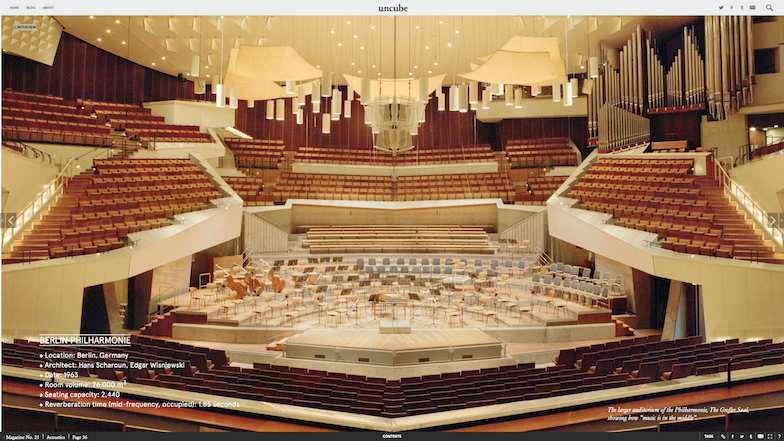

The Berlin Philharmonie is an architectural masterpiece famously conceived from the inside-out around the requirements of its acoustics. Designed by Hans Scharoun, the main 2,440 seater auditorium, the Großer Saal, opened in 1963, but Scharoun died before the second, smaller chamber music hall, the Kammermusiksaal, was built. This was designed in detail by his partner Edgar Wisniewski, who also completed the surrounding suite of public cultural buildings, the Kulturforum.

As is so often the case in these “man behind the throne” scenarios, Wisniewski’s input is rarely acknowledged in textbooks, yet much of the Philharmonie’s success as a building is owed to him. He died in 2007, but ten years ago Sophie Lovell, uncube’s editor-in-chief, got the chance to meet Wisniewski, a tall, striking man in his mid-70s, at the Philharmonie, and talk to him about a working life devoted to translating Scharoun’s simple yet revolutionary ideas – sometimes technically nightmarish to realise – into buildings of world renown.

Dr. Wisniewski, you started your working life as Scharoun’s assistant, helping design the Berlin Philharmonie, but ended up completing and continuing his work yourself.

We worked together for 15 years until he died. During the latter part we were in partnership, which contractually means if one partner dies, the other carries on the work. And that’s what happened. When he died in 1972 I had all these projects, including the rest of the Kulturforum, to continue.

The site was still a bombed-out wasteland then – though 30 years earlier it had been the busiest city centre in Europe.

The final location on the former Kemperplatz is not far from where the old Philharmonie building had been before the war. During construction, the Berlin Wall came down. We stood there on the roof and watched the tanks rolling up and the barbed wire being laid. Some of the main workmen on the site had to come through the sewers to work every day from the eastern part of the city. The building was very close to the border, almost within firing range. Nobody knew what was going to happen next.

How did your partnership with Scharoun come about?

When I finished my studies at the Technical University in Berlin, Rügenberg, one of Scharoun’s assistants, recommended me to him as there was a post available. Of course, I knew who he was and had attended his lectures. I liked how he worked in an organic way; the form of his buildings developing from the inside out. Then the very first project that came up when I began working for him was the competition for the Philharmonie. It was very helpful that I was heavily involved with music. I was in a famous choir at the time, St. Hedwig’s Cathedral Choir, which the Philharmonic Orchestra under [Herbert von] Karajan played with. My knowledge and understanding of the repertoire helped form a good, trusting relationship with Karajan, who was the one that pushed the Philharmonie through. Karajan also told me once he’d originally wanted to be an architect.

So Karajan was a decisive factor in choosing and building Scharoun’s design?

Although the scheme had won first prize in the competition, there were intrigues: people wanting to hinder its construction from the start. The decision to build was won narrowly by a single vote, only after Karajan threatened to leave the orchestra – and Berlin – if it wasn’t built. His support was decisive.

Was this support because of Scharoun’s idea of putting the “music in the middle”?

The trust and understanding between us, Karajan and the musicians were very important because this idea of putting music, the orchestra, at the centre of the hall with everything else circled around it, was new – the Berlin Philharmonie was the first. Scharoun always said that it’s no coincidence that wherever improvised music is played, people immediately form a circle around it, and that this must be translatable to a concert hall. The whole design developed from that premise.

Was the design driven primarily by the acoustics?

Putting the music – the acoustics – in the centre had other important benefits too: Scharoun didn’t want any hierarchies. In the seating, there are only slanting planes and stalls with no dress circle, apart from two galleries for special music performances, and there’s a single foyer for all. The idea of being up close to the action was also important. There are over 2,200 seats in the main hall, yet none is more than 28 metres away from the stage. That’s what’s so special about this space: you are so close to the people making music. This works the other way too: when you stand on the podium you feel how close the audience is, how they demand the best from you. I particularly like to sit in the choir seats behind the orchestra because you are so much inside it all. The whole floor, everything, vibrates there.

Do you think visiting musicians and orchestras look forward to playing here?

Since 1963, practically every great orchestra in the world has played here. But they do have to adjust acoustically. Many of them are used to playing in halls with a shoebox construction, with walls all around. Suddenly, here there is nothing – the flanking walls are relatively low, and some are angled, meaning part of the sound is reflected back to the orchestra so that the musicians can hear each other.

The reflectors in the ceiling are also specifically designed to stop the echoes from the high ceiling. A relatively long, two-second reverberation time in the full hall was originally requested because that is what’s needed for the late Romantic pieces such as Brahms, Brückner, Mahler and Richard Strauss, the tradition of the Berlin Philharmonic orchestra. The only way to get this reverberation is with a large volume, which is why the ceiling is 22 metres above the podium. But then it comes down in a convex sweep towards the audience, who comes up to meet it, like coming up the sides of a valley. Mrs Scharoun said it looked like a vineyard.

I understand it was Lothar Cremer who worked out the acoustics. It must have been an intense collaboration.

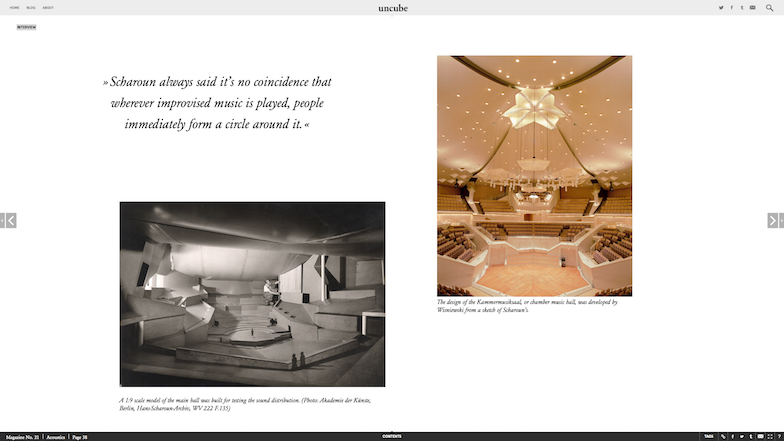

Yes, the first thing he said was that it wouldn’t work! There was nothing to go on. Nobody had built a hall like this before. There were no lasers and computers for measuring like today. We built a big scale model at 1:9 that you could stand in, and they fired a type of acoustic pistol in there, recording the results with microphones.

And the Kammermusiksaal? You built that yourself based on a rough sketch from Scharoun.

I was not only deeply involved with music, I also studied musicology at the Technical University, with lectures from people like Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, one of Schönberg’s students. I’d learnt about the whole development of new music and was able to bring this to the design of the Kammermusiksaal, and it was Scharoun’s wish that I do – he was very open. He made just one sketch of it: not so much a design as an agreement that we make a centrally orientated space. Cremer said it was acoustically more complicated to build than the main hall, but when it was finished we didn’t have to make any acoustic adjustments at all.

How much of the Philharmonie is you and how much is Scharoun?

That’s something I wouldn’t even discuss in private! Many changes had to be made to the original design, to the staircases, the foyer, and so on. I designed a lot in the building. Even the gold aluminium façade is mine.

Was it a burden carrying on Scharoun’s legacy?

Scharoun’s and my own achievements are inextricably bound. From the initial planning of the Philharmonie, I simply moved on to the other big building projects of the Kulturforum. They represent more than 30 years of continual work. I never perceived the work as a burden, more a challenge.

Do you see yourself as having lived in his shadow professionally? His name often only gets mentioned in relation to the Kulturforum ensemble.

Planning the four main buildings of the Kulturforum: the Philharmonie, the Staatsbibliothek, the Staatliche Institut für Musikforschung with the Musikinstrumenten- Museum and the Kammermusiksaal, has been so fulfilling. I perceive Scharoun’s shadow as inspiring, not obliterating. He only lived to see the Philharmonie, but I, on the other hand, can look at the four buildings, remember the battles fought to build them and experience them now, today, filled with music. Any feelings about shadows evaporate.

From uncube magazine issue no. 21: “Acoustics”, edited by Sophie Lovell