“I don’t want your hope. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I do. Every day. And want you to act. I want you to behave like our house is on fire. Because it is.”

Greta Thunberg, World Economic Forum, Davos, January 2019.

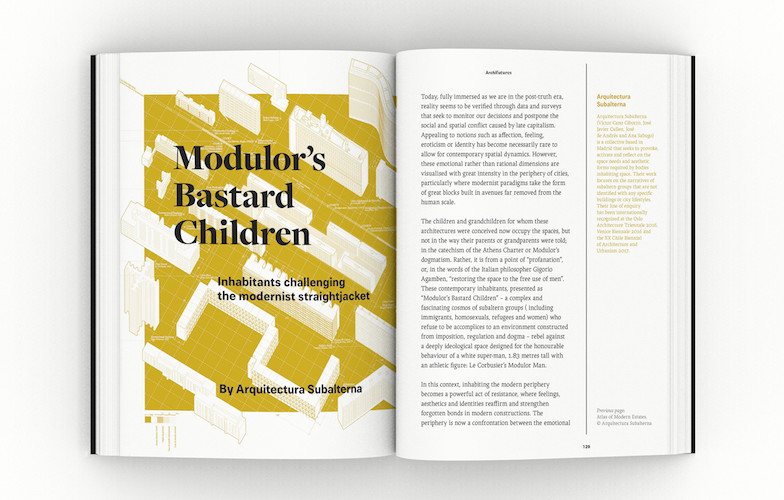

Design, business, politics and economics have belonged together at the very least since the dawn of mechanised mass-production. Modernism, the Deutscher Werkbund and the Bauhaus, for example, may have been about providing a functional, modular, utilitarian living environment for ordinary people: “total architecture” filled with devices to make life easier and better for their inhabitants, but they had just as much to do with reviving economies and the rise of a new kind of political environment as they did with a radically stripped-down design aesthetic.

It is this link between design, industry and social responsibility that fed into the post-war German Economic Miracle (Wirstschaftswunder) in the 1950s where companies that pioneered that wave embraced new forms of design as well. Good design made sense socially, yes, but it also made sense commercially. This “design-driven” approach, incidentally, was picked up many years later by one Steve Jobs who used it as a template to turn around his own failing consumer electronics company Apple and make it the largest information technology company in the world.

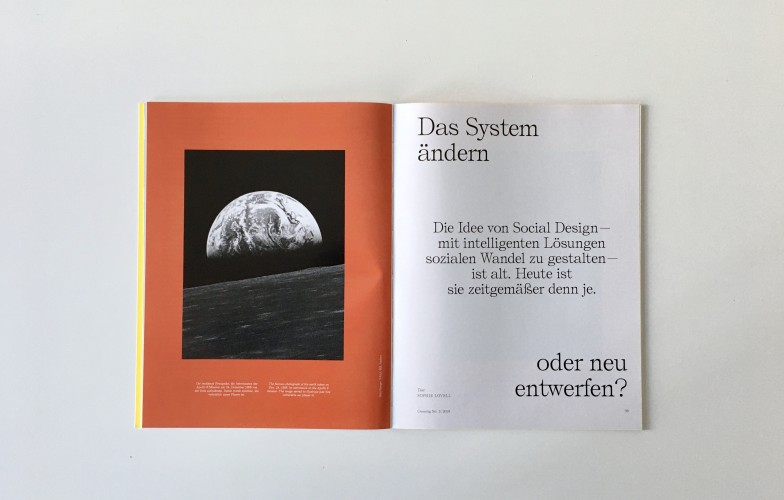

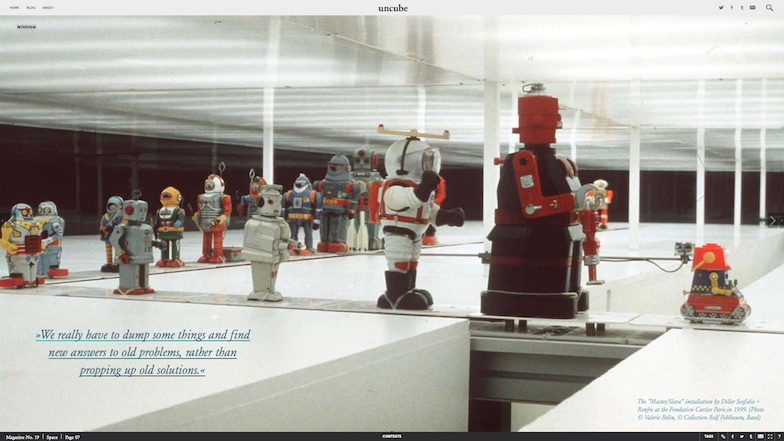

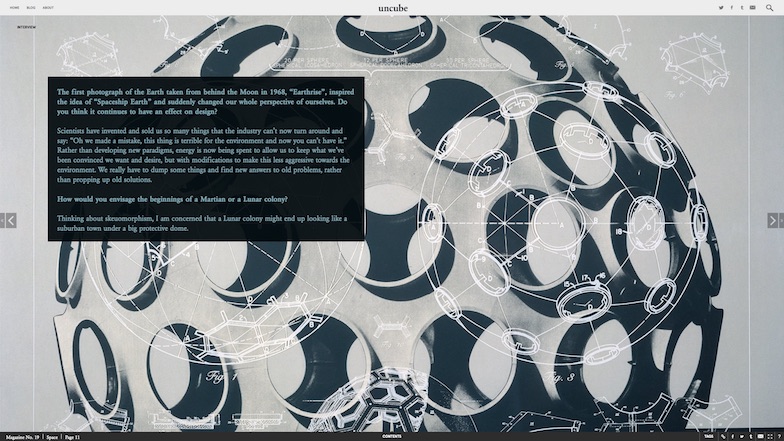

But all this rampant growth came at a human and environmental price. By the 1960s it became clear that the Earth was sick, and our own rampant consumption and greed was the cause. On December 24th, 1968, the astronaut William Anders on the Apollo 8 mission took a colour photograph of the Earth rising behind the Moon. For the first time ever it became blatantly, visibly, clear that all human life shares this one ball with nothing but a thin film of atmosphere separating us from oblivion. In 1969, the influential American architect, designer, theorist and inventor R. Buckminster Fuller published his famous Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth in which he talks about “earthians’ critical moment” in which “All of humanity now has the option to ‘make it’ successfully and sustainably, by virtue of our having minds, discovering principles and being able to employ these principles to do more with less.” The writing was already on the wall – along with the path we needed to take for our salvation – 50 years ago, yet we were already learning to ignore it.

Not long after, at the 1970 International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado – founded in 1951 by Chicago businessman to encourage a closer relationship between art, design and commerce – there was a clash with a new generation who, like Bucky Fuller, had a very different understanding of design and responsibility. Designers, architects and student activists disrupted the week-long event protesting against, in the words of design critic Alice Twemlow (in her 2008 essay A Look Back at Aspen): “its lack of political engagement, its flimsy grasp of pressing environmental issues and its outmoded non-participatory format.” For these protesters, Twemlow goes on: “design was not about the promulgation of good taste or the upholding of professional values; it had much larger social and specifically environmental repercussions for which designers must claim responsibility. Nor, for them, was design only about objects and structures; rather, they understood it in terms of interconnected systems and processes and specifically, within the context of the exploitation of natural resources and unchecked population growth.”

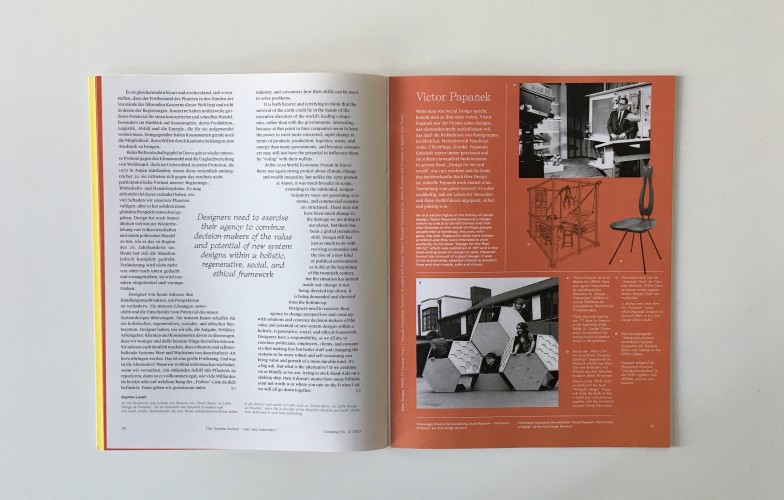

These protesters had a far more inclusive view of design, one that sees design touching on and – more importantly – having responsibility towards all humans and to the rest of the planet. In 1971, the designer Victor Papanek published his book Designing for the Real World. In it he not only called for an inclusive attitude to design, away from commercial goals, a design approach which, he believed, could help change social inequalities by designing for the disadvantaged, but he also said designers had a responsibility to think and work in this way.

But here we are it seems, half a century of further unchecked growth in all directions later, and in wanton ignorance of all warnings, we nonetheless find ourselves in the middle of the biggest crisis humankind has ever faced (or caused): one that threatens our own extinction and all life as we know it on our beautiful blue spaceship, not tomorrow or in some distant future, but now. Design has changed massively in those fifty years, as has technology and science, but our planet’s problems have remained pretty much the same. So what can designers do and what are designers doing to shoulder this responsibility they already knew they had?

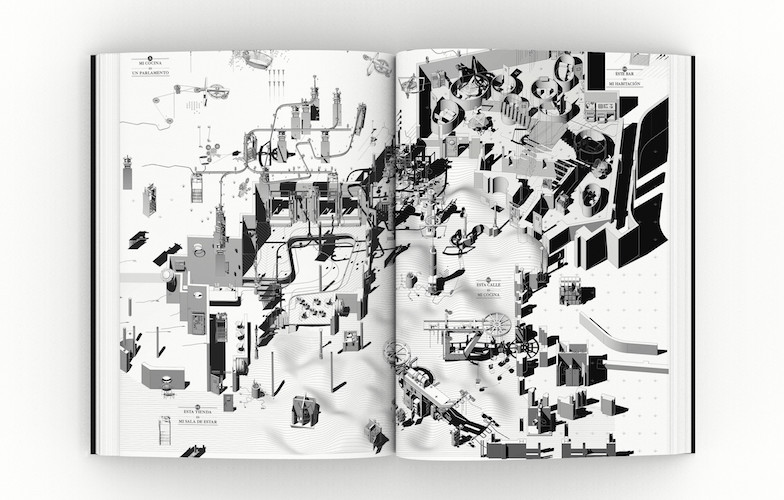

The first step is to acknowledge and work with the change in parameters. Design should now be understood as a systems-based discipline, rather than an object-based one. Back in the nineteenth century, the naturalist John Muir stated: “When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world”. This means the ramifications of our actions are never isolated and often more far-reaching than we consider. It also means that the level of complexity involved in designing and finding solutions can be daunting and mind-boggling. But it also gives hope because thanks to these interconnections we do have opportunities to exert change no matter how vast and complex the system might be.

Human-generated complexity however is still nothing compared to what nature is capable of. So, taking ecology as a model has become an increasingly (excuse the pun) fruitful path for designers. Regenerative design, for example, uses whole systems thinking to design processes that are not only environmentally-friendly and “sustainable”, but which are dynamic, restoring and, renewing their own sources of energy and materials. It is a very different approach to “growth” in the capitalist sense in that it is at once conservative and regenerative. Regenerative design was another idea that came out of the 1970s with the idea of a sustainable, permanent agricultural system called “permaculture” developed by David Holmgren and Bill Mollison in Tasmania. The term was later expanded to mean “permanent culture” since it had social aspects and implications. Today there are entire frameworks based on the idea – particularly in the highly complex realm of building. The Sustainable Project Appraisal Routine (SPeAR), designed by the engineering firm ARUP, for example, is a complexity-managing tool to appraise architecture projects in terms of “key themes such as transport, biodiversity, culture, employment and skills” and allow for the adjustment of “project performance”.

As a result of this better understanding of complexity, there are now many branches and sub-categories of designers from biosynthetic designers, reverse-engineering nature, to virtual reality designers creating entire new worlds. Many thousands of solutions will be needed to change the world for the better, and many millions of people to design and make those changes. The “swarm intelligence” of the planet is required, not just to design solutions but social, political, behavioural and technical as well.

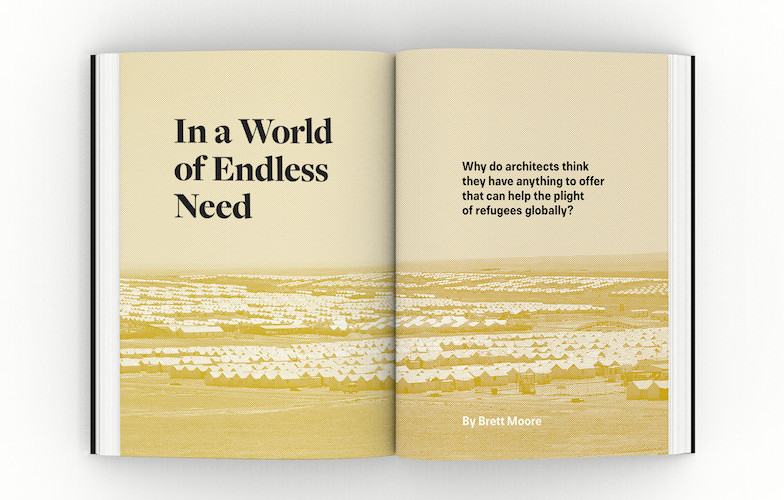

In real terms this means that we are not going to change the refugee crisis by designing, producing and selling flat-pack temporary housing, for example, if we do not change the system that generated and perpetuates the refugee crisis. And we are not going to solve the world’s dependency on fossil fuels by designing and selling cars that run on alternative fuel sources without changing the system and lobbies that perpetuate and profit from fossil fuels – or changing the behaviour of car users. So this means that designers need to engage with the bigger “ecosystems” related to design, connect politically, professionally and socially to design alternative systems in an interdisciplinary fashion. Common examples of such systems on a local scale are new forms of exchange such as time banks, neighbourhood tool-sharing platforms or car-pooling and car-sharing. Also, fair and direct trade networks between producers and consumers of certain goods which can allow greater consumer choice on the ethical and environmental aspects of the products they do buy because they have increasingly less trust in “brands” to do it for them.

The majority of these systems are concerned with rethinking the idea of ownership and how “value” is recognised and socialised. One recent example is a group called Phi from the Strelka Institute in Russia who are using a combination of peer-to-peer blockchain technologies and speculative design to imagine a new, decentralised model for generating and sharing energy rather than having to rely on governments and monopolies to provide reliable and affordable energy sources.

Perhaps instead of asking: how can design improve our lives, we should ask how can design change our behaviour? Tim Brown, CEO of the global design company IDEO believes strongly in the value of using design to change behaviour. Whether it be reducing child respiratory disease by getting children to wash their hands more often or putting the tools for change in the hands of the users in the form of data and analysis apps for example. But changing behaviour to promote more ethical behaviour patterns within social and environmental contexts begs the question: whose values are we promoting and who will benefit from those changes?

Also, fixing behaviour alone will not be effective if we do not change the overriding system governing human activity on this planet – and that system is, like it or not, late capitalism. In his 2013 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the French economist Thomas Piketty argues that the problems of inequality and unequal distribution of wealth that have come with the global capitalist system are not temporary but are the result of structural flaws in and the effect of the system itself. If he is right, we can change behaviour all we like, but if we do not change the system as well, then the overall global situation will not improve.

In April 2018, when the world watched US Congress grilling the CEO of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, on the subject of data misuse, it was interesting to witness a) the spectacular degree of ignorance amongst national government politicians as to how social media actually works and b) that that same government, seemed to expect a for-profit corporation to legislate and lead the way in setting its own ethical standards and policing itself. It felt like witnessing the final abdication of the world’s most powerful nation state from the responsibility for the moral and ethical welfare of itself and its citizens.

The speculative architect Liam Young recently advocated the dissolution of the term “architect”, saying that an architect’s skills are wasted on building buildings – on creating objects – and that that is a good thing: “It means that the profession can find traction in other fields: the architect as a strategist, as politician … as activist or storyteller. Finding ways to operate in other disciplines just gives us more agency.” We all, not just architects, need to push beyond the outdated apparatus of our professions. Although appearances may be to the contrary, we do not need more houses, we do not need more objects, we do not need more stuff. We need new systems. Urgently. And it is agency that designers need to cultivate in these times when trust in our established systems is failing and the environment is in crisis. Designers are, first and foremost, problem-solvers. They need to show politicians, industry and consumers how their skills can be used to solve problems.

It is both bizarre and terrifying to think that the survival of the Earth could lie in the hands of the executive directors of the world’s leading companies, rather than governments. Interesting because at this point in time they seem to have the better potential for more concerted rapid change in terms of products, production, logistics, waste and energy than many governments and because consumers may still just about have the potential to influence them by voting with their wallets. Terrifying because this kind of power is anything but democratic.

At the 2019 World Economic Summit in Davos there was again strong protest about climate change and wealth inequality, but unlike the 1970 protest at Aspen, it was much broader in scope, extending to the outmoded, non-participatory format of the way our governing, economic and commercial systems are structured. There may not have been much change in the damage we are doing to our planet, but there has been a global perspective shift since then. Design also still has just as much to do with reviving economies and the rise of a new kind of political environment now as it did at the beginning of the twentieth century. But now the situation has turned inside-out. Change is not being directed top down, it is being demanded and directed from the bottom up.

Designers need to exercise their agency to change perspectives and come up with solutions and convince decision-makers of the value and potential of new system designs within a holistic, regenerative and social and ethical framework. Designers have a responsibility, as we all do, to convince politicians, employers, clients and consumers that making less, but better, stuff and changing their systems to ones that are more robust and self-sustaining can bring value and growth of a more durable kind. It’s a big ask. But what is the alternative? If we continue on as blindly as we are doing, trying to stick band-aids on a sinking ship, then it doesn’t matter how many billions your net worth is or what your Forbes list rating is. We are all going down together.

Date: 2019

Client: Volkswagen Group Culture "Crossing" magazine No.3

Commissioning editor: Esra Aydin

Images: various