“Indifference towards people and the reality in which they live is actually the one and only cardinal sin in design”

Dieter Rams

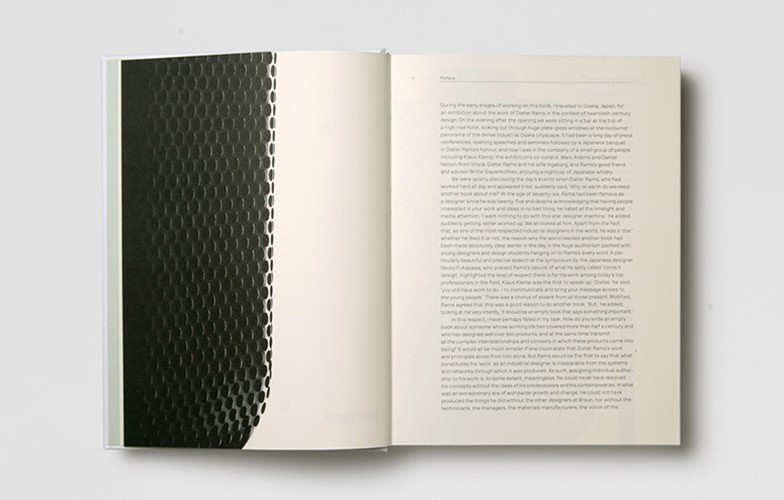

During the early stages of working on this book, I travelled to Osaka, Japan, for an exhibition about the work of Dieter Rams in the context of twentieth-century design. On the evening after the opening we were sitting in a bar at the top of a high-rise hotel, looking out through huge plate-glass windows at the nocturnal panorama of the dense industrial Osaka cityscape. It had been a long day of press conferences, opening speeches and seminars followed by a Japanese banquet in Dieter Rams’ honour, and now I was in the company of a small group of people including Klaus Klemp, the exhibition’s co-curator, Mark Adams and Daniel Nelson from Vitsoe, Dieter Rams and his wife Ingeborg, and Rams’ good friend and advisor Britte Siepenkothen, enjoying a nightcap of Japanese whisky.

We were quietly discussing the day’s events when Dieter Rams, who had worked hard all day and appeared tired, suddenly said, “Why on earth do we need another book about me?” At the age of seventy-six, Rams had been famous as a designer since he was twenty-five and despite acknowledging that having people interested in your work and ideas is no bad thing, he hated all the limelight and media attention.

“I want nothing to do with this star designer machine”, he added, suddenly getting rather worked up. We all looked at him. Apart from the fact that, as one of the most respected industrial designers in the world, he was a “star” whether he liked it or not, the reason why the world needed another book had been made absolutely clear earlier in the day in the huge auditorium packed with young designers and design students hanging on to Rams’ every word. A particularly beautiful and precise speech at the symposium by the Japanese designer Naoto Fukasawa, who praised Rams’ oeuvre of what he aptly called “correct design”, highlighted the level of respect there is for his work among today’s top professionals in the field. Klaus Klemp was the first to speak up: “Dieter”, he said, “you still have work to do, to communicate and bring your message across to the young people”. There was a chorus of assent from all those present. Mollified, Rams agreed that this was a good reason to do another book. “But”, he added, looking at me very intently, “it should be an empty book that says something important”.